Added By: valashain

Last Updated: Administrator

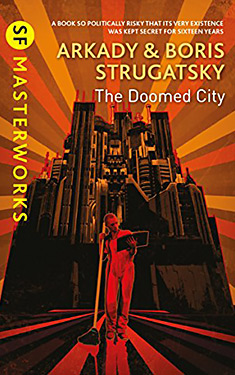

The Doomed City

| Author: | Arkady Strugatsky Boris Strugatsky |

| Publisher: |

Gollancz, 2017 Chicago Review Press, 2016 Original Russian publication, 1989 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Dystopia Human Development Soft SF |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The magnum opus of Russia's greatest science fiction novelists translated into English for the first time

Arkady and Boris Strugatsky are widely considered the greatest of Russian science fiction masters, and their most famous work, Roadside Picnic, has enjoyed great popularity worldwide. Yet the novel they worked hardest on, that was their own favorite, and that readers worldwide have acclaimed as their magnum opus, has never before been published in English. The Doomed City was so politically risky that the Strugatsky brothers kept its existence a complete secret even from their closest friends for sixteen years after its completion in 1972. It was only published in Russia during perestroika in the late 1980s, the last of their works to see publication. It was translated into a host of European languages, and now appears in English in a major new effort by acclaimed translator Andrew Bromfield.

The Doomed City is set in an experimental city whose sun gets switched on in the morning and switched off at night, bordered by an abyss on one side and an impossibly high wall on the other. Its inhabitants are people who were plucked from twentieth-century history at various times and places and left to govern themselves, advised by Mentors whose purpose seems inscrutable. Andrei Voronin, a young astronomer plucked from Leningrad in the 1950s, is a die-hard believer in the Experiment, even though his first job in the city is as a garbage collector. And as increasinbly nightmarish scenarios begin to affect the city, he rises through the political hierarchy, with devastating effect. Boris Strugatsky wrote that the task of writing The Doomed City "was genuinely delightful and fascinating work." Readers will doubtless say the same of the experience of reading it.

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

The trash cans were rusty and battered, and the lids had come loose, so there were scraps of newspaper poking up from under them and potato peels dangling down. They were like the bills of slovenly pelicans that are none too picky about their food. The cans looked way too heavy to lift, but in fact, working in tandem with Wang, it was a breeze to jerk a can like that up toward Donald's outstretched hands and set it on the edge of the truck's lowered sideboard. You just had to watch out for your fingers. And after that you could adjust your mittens and take a few breaths through your nose while Donald walked the can farther in on the back of the truck and left it there.

The damp chill of nighttime breathed in through the wide-open gates, and under the archway a naked, yellow lightbulb swayed on a wire that was furred with grime. In its light Wang's face looked like the face of a man with a chronic case of jaundice, but Donald's face was invisible in the shadow of his wide-brimmed cowboy hat. The chipped and peeling gray walls were furrowed by horizontal slashes and adorned with obscene, life-size depictions of women. Dark clumps of dusty cobwebs dangled from the vaulting, and standing beside the door of the caretaker's lodge was a disorderly crowd of the empty bottles and stewed-fruit jars that Wang collected, carefully sorted, and handed in for recycling...

When there was only one trash can left, Wang took a shovel and a broom and started sweeping up the trash left on the asphalt surface.

"Ah, stop scrabbling around, Wang," Donald exclaimed irritably. "You scrabble around that way every time. It's still not going get any cleaner, is it?"

"A caretaker should be a sweeper," Andrei remarked didactically, twirling the wrist of his right hand and focusing on his sensations: it seemed to him that he had slightly strained a tendon.

"They'll only make it all filthy again, won't they?" Donald said with loathing. "Before we've even turned around, they'll foul it up worse than before."

Wang tipped the trash into the last can, tamped it down with the shovel, and slammed the lid shut. "Now we can do it," he said, glancing around the arched passage. The entrance was clean now. Wang looked at Andrei and smiled. Then he looked up at Donald and said, "I'd just like to remind you --"

"Come on, come on!" Donald shouted impatiently.

One-two. Andrei and Wang lifted the can. Three-four. Donald caught the can, grunted, gasped, and lost his grip. The can lurched over and crashed down onto the asphalt on its side. Garbage flew out across ten meters as if it had been shot from a cannon. Actively disgorging as it went, the can clattered into the courtyard. The reverberating echo spiraled up to the black sky between the walls.

"God al-fucking-mighty and the Holy Spirit," said Andrei, who had barely managed to leap out of the way. "Damn your fumblefingers!"

"I just wanted to remind you," Wang said meekly, "that one handle's broken off this can."

He took the broom and shovel and set to work, and Donald squatted on the edge of the truck bed and lowered his hands between his knees. "Dammit..." he muttered in a dull voice. "Damned mean trick."

Something had clearly been wrong with him for the last few days, and on this night in particular. So Andrei didn't start telling him what he thought about professors and their ability to do real work. He went to get the can and then, when he got back to the truck, he took off his mittens and pulled out his cigarettes. The stench from the open can was unbearable, so he lit up quickly and only then offered Donald one. Donald shook his head without speaking. His mood needed a lift. Andrei flung the burned match into the can and said, "Once upon a time in a little town there lived two night-soil men -- father and son. There weren't any sewers there, only pits full of slurry. And they scooped that shit out with a bucket and poured it into their barrel, and what's more, the father, as the more experienced specialist, went down into the pit, and the son handed the bucket down to him from above. Then one day the son lost his grip on the bucket and dumped it back on his old man. Well, his old man wiped himself down, looked up at him, and said bitterly, 'You're a total screwup, a real lunkhead. No good for anything. You'll be stuck up there your whole life.'"

He was expecting Donald to smile, at least. Donald was generally a cheerful individual, sociable -- he never got downhearted. There was something of the combat-veteran-turned-student about him. But this time Donald only cleared his throat and said in a dull voice, "You can't shovel out all the cesspits."

And Wang, scrabbling beside the can, reacted in a way that was really strange. He suddenly asked in a curious voice, "So what does it cost where you're from?"

"What does what cost?" asked Andrei, puzzled.

"Shit. Is it expensive?"

Andrei chuckled uncertainly. "Well, how can I put it... It depends whose it is."

"So you've got different kinds there then?" Wang asked in amazement. "It's all the same where I'm from. So whose shit is most expensive where you're from?"

"Professors'," Andrei replied immediately. He simply couldn't resist it.

"Ah!" Wang tipped another shovel-load into the can and nodded. "I get it. But out in the country there weren't any professors, so we only had one price: five yuan a bucket. That's in Szechuan. But in Kiangsi, for instance, prices ran up to seven or even eight yuan a bucket."

Andrei finally realized this was serious. He suddenly felt an urge to ask if it was true that when a Chinaman was invited to dinner, he was obliged to crap on his host's vegetable plot afterward -- but, of course, it felt too awkward to ask about that.

"Only how things are now where I'm from, I don't know," Wang continued. "I wasn't living out in the country at the end... But why is professors' shit more expensive where you're from?"

"I was joking," Andrei said guiltily. "No one even trades in that stuff where I'm from."

"Yes they do," said Donald. "You don't even know that, Andrei."

"And that's yet another thing you do know," Andrei snapped.

Only a month ago he would have launched into a furious argument with Donald. It annoyed him immensely that again and again the American kept telling them things about Russia that Andrei didn't even have a clue about. Back then, Andrei was sure that Donald was simply bluffing him or repeating Hearst's spiteful tittle-tattle: "Take that garbage from Hearst and shove it!" he used to yell, shrugging it all off. But then that jerk Izya Katzman had appeared, and Andrei stopped arguing; he just snarled back. God only knew where they'd picked it all up from. And he explained his own helplessness by the fact that he'd come here from the year 1951, and these two were from '67.

"You're a lucky man," Donald said suddenly, getting up and moving toward the trash cans beside the driver's cabin.

Andrei shrugged and, in an effort to rid himself of the bad taste left by this conversation, put on his mittens and started shoveling up the stinking trash, helping Wang. Well, so I don't know, he thought. It's a big deal, shit. And what do you know about integral equations? Or Hubble's constant, say? Everyone has something he doesn't know...

Wang was stuffing the final remains of the trash into the can when the neatly proportioned figure of police constable Kensi Ubukata appeared in the gateway from the street. "This way, please," he said over his shoulder to someone, and saluted Andrei with two fingers. "Greetings, garbage collectors!"

A girl stepped out of the darkness of the street into the circle of yellow light and stopped beside Kensi. She was very young, no more than about twenty, and really small, only up to the little policeman's shoulder. She was wearing a coarse sweater with an extremely wide neck and a short, tight skirt. Thick lipstick made her lips stand out vividly against her pale, boyish face, and her long blonde hair reached down to her shoulders.

"Don't be frightened," Kensi told her with a polite smile. "They're only our garbage collectors. Perfectly harmless in a sober state... Wang," he called. "This is Selma Nagel, a new girl. Orders are to put her in your building, in number 18. Is 18 free?"

Wang walked over to him, removing his mittens on the way. "Yes," he said. "It's been free for a long time. Hello, Selma Nagel. I'm the caretaker -- my name's Wang. If you need anything, that's the door to the caretaker's lodge, you come here."

"Let me have the key," Kensi said, and saluted again. "Come on, I'll show you the way," he said to the girl.

"No need," she said wearily. "I'll find it myself."

"As you wish," Kensi said, and saluted again. "Here is your suitcase."

The girl took the suitcase from Kensi and the key from Wang, tossed her head, and set off across the asphalt, clattering her heels and walking straight at Andrei.

He stepped back to let her past. As she walked by, he caught a strong smell of perfume and some other kind of fragrance too. And he carried on gazing after her as she walked across the circle of yellow illumination. Her skirt was really short, just a bit longer than her sweater, her legs were bare and white -- to Andrei they seemed to glow as she walked out from under the archway into the yard -- and in that darkness all he could see were her white sweater and flickering white legs.

Then a door creaked, screeched, and crashed, and after that Andrei mechanically took out his cigarettes again and lit up, imagining those delicate white legs walking up the stairs, step by step... smooth calves, dimples under the knees, enough to drive you crazy... He saw her climbing higher and higher, floor after floor, and stopping in front of the door of apartment 18, directly opposite apartment 16... Dam-naa-tion, I ought to change the bedsheets at least; I haven't changed them for three weeks, the pillowcase is as gray as a foot rag... But what was her face like? Well, I'll be damned, I don't remember anything about what her face looked like. All I remember are the legs.

He suddenly realized that no one was saying anything, not even the married man Wang, and at that moment Kensi started speaking. "I have a first cousin once removed, Colonel Maki. A former colonel of the former imperial army. At first he was Mr. Oshima's adjutant and he spent two years in Berlin. Then he was appointed our acting military attaché in Czechoslovakia, and he was there when the Germans entered Prague..."

Wang nodded to Andrei. They lifted the can with a jerk and successfully shunted it onto the back of the truck.

"... And then," Kensi continued at a leisurely pace, lighting up a cigarette, "he fought for a while in China, somewhere in the south, I think it was, down Canton way. And then he commanded a division that landed on the Philippines, and he was one of the organizers of the famous 'march of death,' with five thousand American prisoners of war -- sorry, Donald... And then he was sent to Manchuria and appointed head of the Sakhalin fortified region, where, as it happens, in order to preserve secrecy he herded eight thousand Chinese workers into a mine shaft and blew it up -- sorry, Wang... And then he was taken prisoner by the Russians, and instead of hanging him or handing him over to the Chinese -- which is the same thing -- all they did was lock him up for ten years in a concentration camp..."

While Kensi was telling them all this, Andrei had time to clamber up onto the back of the truck, help Donald line up the cans there, raise the sideboard and secure it, jump back down onto the ground, and give Donald a cigarette, and now the three of them were standing in front of Kensi and listening to him: Donald Cooper, long and stooped, in a faded boilersuit -- a long face with folds beside the mouth and a sharp chin with a growth of sparse, gray stubble; and Wang, broad and stocky, almost neckless, in an old, neatly darned wadded jacket -- a broad, brownish face, little snub nose, affable smile, dark eyes in the cracks of puffy eyelids -- and Andrei was suddenly transfixed by a poignant joy at the thought that all these people from different countries, and even from different times, were all here together and all doing one thing of great importance, each at his own post.

"... Now he's an old man," Kensi concluded. "And he claims that the best women he ever knew were Russian women. Emigrants in Harbin." He stopped speaking, dropped his cigarette butt, and painstakingly ground it to dust with the sole of his gleaming ankle boot.

Andrei said, "What kind of Russian is she? 'Selma'-- and 'Nagel' too?"

"Yes, she's Swedish," said Kensi. "But all the same. The story came to me by association."

"OK, let's go," Donald said, and climbed into the cabin.

"Listen, Kensi," said Andrei, taking hold of the cabin door. "Who were you before this?"

"An inspector at the foundry, and before that, minister of communal --"

"No, not here, back there."

"Aah, there? Back there I was literary editor for the journal Hayakawa."

Donald started the motor and the vintage truck began shaking and rattling, belching out thick clouds of blue smoke.

"Your right sidelight isn't working!" Kensi shouted.

"It hasn't worked in all the time we've been here," Andrei responded.

"Then get it fixed! If I see it again, I'll fine you!"

"They set you on to hound us..."

"What? I can't hear!"

"I said, catch bandits, not drivers!" Andrei yelled, trying to shout over the clanging and clattering. "What's our sidelight to you? When are they going to send all you spongers packing?"

"Soon," Kensi said. "Any time now -- it won't be more than a hundred years!"

Andrei threatened Kensi with his fist, waved good-bye to Wang, and plumped into the seat beside Donald. The truck jerked forward, scraping one side along the wall of the archway, trundled out onto Main Street, and made a sharp turn to the right.

Settling himself more comfortably, so that the spring protruding from the seat wasn't pricking his backside, Andrei cast a sideways glance at Donald, who was sitting up straight, with his left hand on the steering wheel and his right on the gearshift; his hat was pushed forward over his eyes, his pointed chin was thrust out, and he was driving at top speed. He always drove like that, "at the legal speed limit," never giving a thought to braking at the frequent potholes in the road, and at every one of those potholes the trash cans in the back bounced heavily, the rusted-through hood rattled, and no matter how hard Andrei tried to brace himself with his legs, he flew up in the air and fell back precisely onto the sharp point of that damned spring. Previously, however, all this had been accompanied by good-humored banter, but now Donald didn't say anything, his thin lips were tightly compressed, and he didn't look at Andrei at all, which made it seem like there was some kind of malicious premeditation in this routine jolting.

"What's wrong with you, Don?" Andrei asked eventually. "Got a toothache?"

Donald twitched one shoulder briefly and didn't answer.

"Really, you haven't been yourself these last few days. I can see it. Maybe I've unintentionally offended you somehow?"

"Drop it, Andrei," Donald said through his teeth. "Why does it have to be about you?'

And again Andrei fancied that he heard some kind of ill will, even something offensive or insulting, in these words: How could a snotty kid like you offend me, a professor? But then Donald spoke again.

"I meant it when I said you were lucky. You really are someone to be envied. All this just kind of washes right over you. Or passes straight through you. But it runs over me like a steamroller. I haven't got a single unbroken bone left in me."

"What are you talking about? I don't understand a thing."

Donald said nothing, screwing up his lips.

Andrei looked at him, glanced vacantly at the road ahead, squinted sideways at Donald again, scratched the back of his head, and said disconcertedly, "Word of honor, I don't understand a thing. Everything seems to be going fine --"

"That's why I envy you," Donald said harshly. "And that's enough about this. Just don't take any notice."

"So how am I supposed to do that?" said Andrei, seriously perturbed now. "How can I not take any notice? We're all here together... You, me, the guys... friendship is a big word, of course, too big... well then, simply comrades... I, for instance, would tell you if there was something... After all, no one's going to refuse to help, are they! Well, you tell me -- if something happened to me and I asked you for help, would you refuse? You wouldn't, would you, honestly?"

Donald's hand lifted off the gearshift and patted Andrei gently on the shoulder. Andrei didn't say anything. His feelings were brimming over. Everything was fine again, everything was all right. Donald was all right. It was just a fit of the blues. A man can get the blues, can't he? It was simply that his pride had reared its head. After all, the man was a professor of sociology, and here he was down with the trash cans, and before that he was a loader. Of course, it was unpleasant and galling for him, especially since he had no one to take these grievances to -- no one had forced him to come here, and it was embarrassing to complain... It was easily said: Make a good job of anything you're given to do... Well, all right. Enough of all this. He'd manage.

Copyright © 1989 by Arkady Strugatsky

Copyright © 1989 by Boris Strugatsky

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details